One More Loop through the Village

![]()

That awkward snippet of time between Christmas and New Year’s is what I often refer to as the Skin Flap Days. You really don’t know what to do with it. If you get a new fly rod for Christmas, likely you stand in your front yard casting away. Neighbors can’t resist the urge to slow down as they roll past and shout, “Catching anything?” This type of low-level humor is the worst, but even lower are some of the experiments I’ve tried to pass this string of time. I’ve gone to Annapolis, Md., to eat oysters. Once I drove to the Four Corners and shopped for pottery but didn’t buy any. This year I decided to take this time and spend it wisely. Bucking tradition and thumbing my nose at social norms, I opted to go to Magdalena Bay on the Baja Peninsula to pass The Skin Flap. Dean, a friend from college, agreed to come along. But he agreed in July. As December approached, the weight of family obligations began to press upon him like an anvil. He and his family live just outside of Richmond, Va., meaning Dean had to fly multiple legs just to get to Loreto, our jumping off point. In mid-December he put up a simple Christmas tree and strung banisters with festive lights. He told his wife he wasn’t about to put up a second tree, nor was he going to un-box and deploy the blow-up Santa and corresponding reindeer. He admitted to me that he felt like a lout as he packed jackets and sunblock in his carry-on.

Did you know that 144 men, on average, die from falls while stringing up Christmas lights each year in America?” I spoke. “Thousands are injured.”

Mag Bay Lodge is a full-service outfitter in Puerto San Carlos, a gritty fishing town still dedicated to shrimping and scalloping. A three-hour shuttle from Loreto allowed Dean and me to catch up. Upon arrival we met Allie, who would cook for us all week, then we decided to walk the streets. Walking the streets, it turns out, is what we did mostly when we weren’t fishing. Puerto San Carlos is not a resort town; there are neighborhood restaurants and tiendas, but no Senor Frogs, no open-air shops pushing kitsch. The family-owned hotels and shops seemed on pause as we moved through the avenues, stopping at a sand berm that overlooks the estuary. It was low tide. Egrets. Lots of egrets. Workers at the fish processing plant were going full tilt. We noticed several businesses advertising whale watching, eco-tours and “snorkeling with marlins.” I had never heard of such a thing, snorkeling with billfish. I had always thought of marlin and sailfish as secretive, solitary creatures. But here, just outside Mag Bay, great schools of marlin gather each year to meet the migrating sardine runs. If you’ve ever watched underwater footage of striped marlin gorging on bait balls, the footage likely came from these waters.

Mixed-breed dogs bum-rushed us, yapping and snarling as we walked the sandy streets. Most were squirts. If you turned to face them head-on, they shrank and skulked away. The dominant boat in the yards was the fiberglass panga—no floors, no extraneous electronics, a makeshift boom with a running light—the workhorse you see all over Mexico and beyond. A church group was selling churros, still hot from the grease. We bought a sack and continued our walk. The smell of resin was overpowering. We wandered to a boatyard where six new pangas were being sanded and outfitted. Back at the lodge we met Denny, our guide for the next several days. Denny grew up in the area but holds dual citizenship and fishes salmon commercially in Alaska during the summer. In a few weeks, he told us, he would switch from guiding fishermen to guiding tourists who flock to Puerto San Carlos to catch the whale migration. “These whales come right up to the boat—scratch their backs on the boat sometimes, move it around,” said Denny.

Magdalena Bay is where California Gray Whales come each year to rear their calves. The modern history of the area dates back to the whaling days. Between 1855 and 1865, American, Dutch, and French whalers killed some 1,250 grays here. Of course, today whales are protected, and their much-anticipated annual return brings tourists and shutterbugs. This injects money into an economy that has been devastated lately by tropical storms and COVID. But for Dean and me, it was fishing. We had vague ideas of whacking a few “eaters” and shipping the fillets back to the States. I employed The Zoby Method, which is to stuff a cooler box into my largest duffle (think of a snake swallowing an egg) and bring my own fillet knife. Dean didn’t bring a cooler; he was still a little stunned that he had left his family in the height of what is generically called The Holidays.

“Jeez, when I was your kids’ age the last thing i wanted to do was hang out with my parents,” I said. “Yeah. But still.”

I read for years about the diversity of this fishery. Inside the bay are vast estuaries complete with mangroves and tidal flats. Walking around town you notice that parking lots are not asphalt but pulverized scallop and clam shells. Conchs are cemented to the walls around houses as a sort of improvised security measure. In the evenings, shrimpers head out for a night of dragging nets. I once lived on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and the faraway sand dunes between the village and the Pacific reminded me of the dunes I saw as a child, but without the million-dollar homes blocking the view. Seagirt and authentic, Puerto San Carlos seems like the last place on earth that has stayed true to its roots. No cruise ships. No putt-putt golf. Many of the men wear white rubber boots associated with commercial fishing as they top off their gas tanks, whistle to each other from across the streets, hustle home with a fresh stack of homemade tortillas from the tiny factory where a pretty girl works all day, her thick hair tied back in a ponytail. Denny picked us up at exactly 6:30 am. The plan was to fish the estuary and hit the outside later in the week. The wind was blasting a legitimate 20 knots and I didn’t want to be out at sea in that kind of weather. Neither did Dean. Once, a few years back, we did an overnight halibut trip in eight-foot seas. The fish were biting, but with the lurching deck, it was impossible to gaff them and haul them aboard. “This first spot holds halibut and corvina—we’ll try here,” said Denny. He throttled down and we slid into the mouth of a canal. Halibut? I knew they were possible, but I usually associate them with the Pacific Northwest. The species I was most interested in, however, was the Pacific black snook, or robalo, as they are known in Mexico.

Trophy fish for globe-trotting anglers, the robalo is enigmatic, powerful, and known to crush streamers. I had a baggy of new snook flies, but Denny had us casting swim baits with light spinning rods. Sooner or later, I’d ask him if it was okay for me to try with my fly rod. Immediately, Dean and I began to catch spotted bay bass, lots of them. We couldn’t resist the opportunity to revive the old competitive spirit we once harbored in college where we played racquetball into the wee hours of the night, until the janitors told us we had to leave the gym. “Okay, guys, let’s try another spot,” said Denny, after we had boated over a dozen bass, but nothing else. “I have other estuaries—I want to move.” We buzzed through confusing mazes of mangroves. Shorebirds blew out of the marsh in our wake. After a few miles, Denny throttled down and told us to start casting toward the mangroves. Something huge boiled. I was gripping the spinning rod, trying to hold on, while Denny backed the panga away from the mangroves. The fish fought like a king salmon, digging down, making unrelenting, stubborn runs. It was a palometa, a jack of sorts, with delicate stripes, a fish that vibed permit, but has a mouth only a mother could love. A great eating fish (or so they tell me), my palometa went into the fish box. Next, Dean hooked a giant that screamed drag. Denny timed it perfectly again, hitting the throttle so the fish couldn’t make the mangroves and snap the line. I was thinking it was another palometa, but when it rolled on the surface we recognized the obvious black lateral line of a Pacific snook. “Robalo!” cried Denny. I did the netting and didn’t panic when the great fish wouldn’t quite fit into the net. Dean, who doesn’t read much by way of the outdoor press, didn’t know what to make of Denny’s hooting and back-slapping and was wholly unaware that he had landed a trophy fish. We were taking pictures when another boat—the only one we encountered all day—pulled up with two fly fishermen from Nevada, here to catch snook. They had been unsuccessful in two days of casting, but still caught a variety of species each day.

Another spot revealed a massive school of fish in a particularly tidal section of the estuary, the current ripping. These fish turned out to be corvina, a member of the drum family. I recall reading one of my favorite fly-fishing authors, Scott Sadil, who pretty much wrote the book on fly fishing the Baja. I remember his tales of catching corvina in the surf and roasting them on charcoal fires somewhere on the beach. Thus inspired, I switched over to my 9-weight with a sinking line. The fish hammered Clousers. For several hours we drifted over the school, catching and releasing dozens of feisty corvinas, throwing 10 or so fat ones in the fish box. Upon closer inspection, these fish reminded me of the sea trout I caught on the East Coast. My mother would get up early and drive me to Nags Head Fishing Pier, where I’d go through two dozen bloodworms catching spots and croakers. The prize, back then, was the sea trout. These corvina had the same sleek shape, an oversized tail, and two or three sharp teeth that tore through my Clousers, making me often replace flies. Boating back to town with our feet up on the gunnels and Denny at the helm, Dean and I reflected on the ridiculous amount of fish (and species) we had caught. Suddenly, Denny slowed the boat. He called out in Spanish. There, in the heavy chop, was a swimmer. We were better than a half-mile from shore. The swimmer wore a wetsuit and gripped a stainless-steel knife in a gloved hand. He had a kickboard and a mesh bag. There was a little red flag duct-taped to his foam kickboard. He climbed aboard and we took him towards shore, where his truck was parked on the sand. Denny knew the guy. In his bag were scallops, already liberated from their shells. I guess the fisherman processed his catch on the board between dives.

The scallop diver offered Dean and me a raw scallop each. Who were we to refuse? It was crunchy and wild. He opened another pouch and showed us several yellow-gold seahorses. These he would sell for three dollars if we wanted them. Dean and I were speechless. All these years we had associated masculinity with college football and Rocky movies. And here was this wild scallop man, totally unaware and without ego, just making a living. Dean and I come from a culture where young people game and become paralyzed when they misplace their cell phones. The scallop diver seemed like a throwback to other times, an ode to self-reliance. We didn’t take his picture or ask his name. “Adios,” I squeaked as the man flopped back into the sea and swam out of our lives. “I used to do that back in the day,” said Denny. “We all did. Dangerous.” He shook his head. “Back then we could get ten kilos, easy. These days it’s hard to get just one kilo. And we’re talking about four hours of work, swimming and diving 20 feet down each time.” The theory of rasquachismo, developed by Chicano scholar Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, is the urge to resist poverty and oppression by hybridizing and responding with resourcefulness and creativity. It is, essentially, a celebration of the underdog. It’s easy to come to a place like this and remark on the poverty, the make-shift improvements on the shrimp boats, the cinderblock houses perpetually under construction. But if you don’t see the greatness—the beauty—you’re missing the point. All night, as Dean and I drank Heinekens in the lodge, the thumping sound of traditional Mexican music swam past our block.

We talked about the great variety of fish we caught that day: grouper, snook, pompano, halibut, palometa, bay bass and corvina. And we talked about things like ethnocentrism and what makes happiness. Did we, as we left our beloved alma mater and went into the world, make the correct choices? “I live in a town of 60,000 and we have no bakery,” I said to Dean. “There are three here. Can someone explain that to me?” Can you call this a poor community when they eat the best seafood in the world whenever they want? When they make their living by their own hands? When they are among friends, fishing mostly? When, by the sounds of the laughter and happy music, they celebrate and tolerate each other in ways that seem impossible today in my country? Next morning, we boarded the lodge’s big boat, a 27-foot Boston Whaler. Denny worked as deck hand while Aldo drove the boat. Our first stop was just off Magdalena Island, a tiny fishing community near the boca where the bay meets the open sea. We bought 30 mackerel from a fisherman who had been out all night, catching bait. We paid two bucks a piece, thus saving us the time we’d have to spend chasing it ourselves. Drifting over a rock pile just 100 feet below, we caught yellowtail amberjack in the 10- to 20-pound class. Soon, the fleet of pangas from Magdalena Island joined us. These fishermen used hand lines, and the building chop often made it look like they were riding bucking horses. Upon hooking a fish, their arms moved in a graceful upward movement that gave no slack. It looked like they were doing the backstroke or, having denounced capitalism for good, reaching into their front pockets and tossing their wallets into the air. I missed several fish because I was focusing on the fishermen and their tiny boats. Some of them fished alone. Others had their sons or grandsons with them. They smoked cigarettes. They caught five fish for every one Dean and I managed with our modern equipment. “Don’t compare yourself to these guys— they do this every day,” joked Denny. There were enough yellowtails to go around, but still, I couldn’t help wondering what their lives were like, living out on the edge of the Pacific.

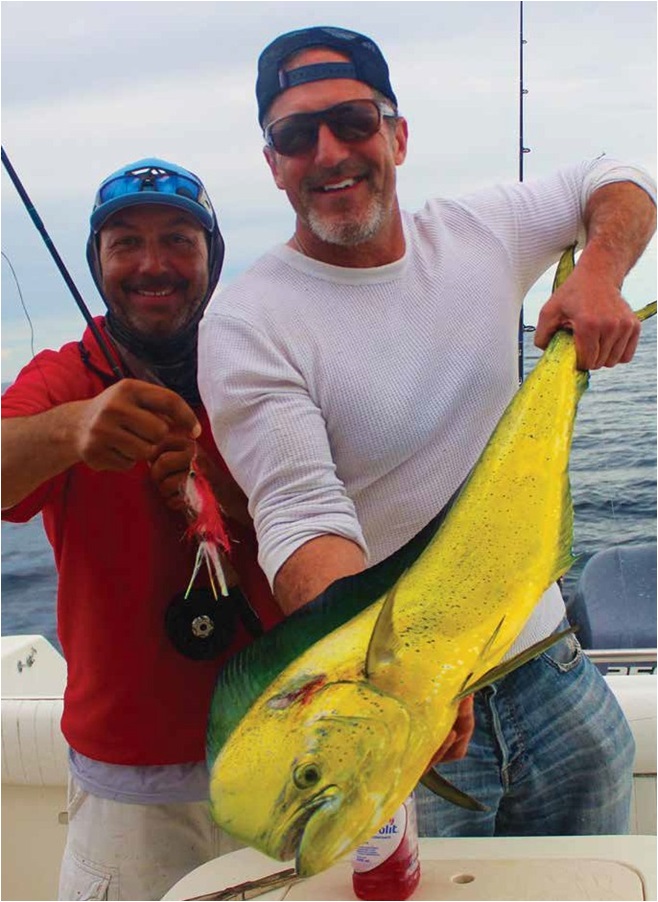

Did they realize restaurants charge eight bucks for two small pieces of yellowtail, or Hamachi, as it is rebranded by the time it reaches your plate? Of course they know. Did they ever get down to Cabo or La Paz to see the high-end restaurants where most of these fish end up? It’s just five hours by car. But there are other ways of measuring distance. I had the passing thought that celebrities get to eat this fish at the most exclusive restaurants in the world. Before I could launch into a treatise on egalitarianism, a yellowtail grabbed my bait and made my drag sing. Of course, I lost the fish. Or maybe it was plucked off my line by one of the lobos that showed up with the fishing fleet. Each time a sea lion surfaced nearby, Denny or Aldo stomped on the deck of the Boston Whaler and whistled. It worked, sort of, but when we found a school of yellowtails and couldn’t get them to the boat without a particular hungry sea lion intervening, Denny said we should move near the fleet of pangas. “Let’s share this sea lion with those other guys,” he said. After the yellowtails, we trolled for Dorado just outside. Quickly, Aldo found them. Dean held the door open while Denny shoved the wild fish into the box. “Those crazy fish. I like to leave them in the box for a while and deal with the hooks later,” said Denny. The winter sun was setting over the Pacific. It was December 28th and we were all wearing T-shirts. Let’s head to the house to see what Allie has for dinner, we said. Aldo and Denny looked puzzled. “If I go home too early, my wife will make me do the dishes,” said Denny. Two days fishing on the Boston Whaler meant Dean and I had enough fillets to cause problems shipping back to the States; even The Zoby Method, which relies on a Styrofoam box capable of handling 50 pounds of fish, was not enough to contain our great harvest.

On New Year’s Eve, Allie made ceviche from a Dorado I caught on my fly rod. She was spending the night with her family, but first prepared enough food to hold us over, even a platter of sashimi. There were no bars or restaurants open, so Dean and I planned a quiet night at the lodge. Scheduled to head back to Loreto the next morning, we had already thanked Denny and Aldo, and the staff at Mag Bay Lodge, spreading 20s around as if somehow it made us even. The guys who processed our fish scrubbed out a huge cooler for us to use on our drive to Loreto. We wanted to wander the streets of Puerto San Carlos to absorb it, to study it. How do you define happiness, I asked Dean, as we walked the sandy streets. “Has life changed so much since we were in college and talked about these things?” “We didn’t talk about this—we only partied,” he reminded me. We ventured down to the pier where the Boston Whaler was tied up. Kids were side-arming oyster shells into the marsh, making them skip four, five, six times. It had rained and great pools of standing water swamped the little Hondas and Toyotas, or made the drivers find alternative routes. The 4-by-4 trucks, though, plunged through. We saw families gathering in their yards.

The street dogs seemed less vicious than before. People grilled almejas chocolatas, or chocolate clams, which you can buy here, but not where Dean and I come from. Knots of teenagers stood around their trucks and blasted traditional music at incredible decibels. Someone fired a Roman candle. More trucks cruising. We stopped at a bakery and bought a sack of pastries for 40 pesos. There was no way to watch the college football games back in the U.S. and we were fine with that. Dean went into his room and talked to his wife on the phone. I sat at the kitchen table and organized my fly box, rinsing my fly line in the sink to flush out the saltwater. Before it went totally dark, we did one more loop through the village. The parties were mostly small family gatherings. There were no televisions, only radios. People waved to us. The murals on the cement walls showed whales. And yellowtails. You could smell seafood and barbecued meats. All night, the happy, pulsing sounds of Mexican music blasted from the streets just outside the lodge. Perhaps it was rasquache at play, with a dash of humor aimed at the gringos who wanted to go to bed at 8:30 on the final night of 2021. Perhaps it was the same guy driving around town with his radio up to the max as a sort of public service. His girlfriend by his side, he wore a straw cowboy hat and his best boots, polished specifically for this night. Or perhaps it was none of these things, but simply a celebration of how quickly time slips past.

IF YOU GO

Toby Larocque operates Mag Bay Lodge (info@magbaylodge.com or 805-757- 4999), which has room for seven anglers and might be the grandest house in Puerto San Carlos. Your trip is all inclusive. We were picked up at the airport in Loreto, then driven across the Baja to Puerto San Carlos, on the Pacific side. All meals were expertly prepared by our in-house chef and the staff was incredibly accommodating. I suggest you come during the Skin Flap between Holidays. The hotels are empty, and you have your choice of seats at the cantina. But there is no college football to be seen, so you’ll have to watch soccer. Or, if you wait a few weeks later, you might be able to fish the estuaries and catch the arrival of the first gray whales and the corresponding photographers who follow them. We arrived in Mag Bay during the “off season” but found the estuary fishing and deep-sea fishing action-packed. Yellowtails were thick in the boca, and just outside the Dorado were so thick it was easy to troll them up whenever we wanted. We did one day in the estuary and two in the Pacific. If I were to go back, I’d probably ask Toby for two days in the estuary and one in the big water. Catching corvina, one after another, with a chance at a trophy snook, is something most fly fishermen can only dream about. Alaska Airlines and American fly into Loreto. Loreto sits on the Sea of Cortez and is a fishing destination. I spent several days wandering around Loreto, a pleasant city of just 22,000, with restaurants and cafes at every turn. I even booked a daytrip for roosterfish and caught several, which I returned unharmed to the sea. In Loreto I fished with Loreto Sea and Land Tours (info@ toursloreto.com) and stayed at the lovely, Spanish-colonial Posada de Las Flores (reservation@posadadelasflores.com). Bring your nine weight and a box of Clousers in white and chartreuse. I used a sinking line with a tapered big game leader in twenty-pound test. Crab and shrimp patterns work well too, but the chartreuse Clouser rules. Make sure you sample the local shrimp and the famous chocolate clams, or alemajas chocolatas, while you’re in town. Whether you are in Puerto San Carlos, on the Pacific side, or Loreto, on the Sea of Cortez, these shellfish are extremely popular and available. I tried them several ways, but grilled with garlic, breadcrumbs, and butter, “Don Caesar Style”, was my favorite.